What is the difference between an engraving, an etching, a dry point technique and a mezzotint? It is not essential for a framer to be an expert in printing techniques but an all round knowledge can be useful. Especially with graphics.

An artist can either create an original piece of artwork, like a water-colour, an oil painting or a pastel drawing or reproduce them as series of so called "limited editions" such as an etching, an engraving, a lithograph or a silk-screen.

In order to guarantee their value, the number of reproductions is limited, each reproduction numbered and the plate from which they are copied destroyed. This is usually done by scoring it. Sometimes however, further impressions will be taken from a cancelled or worn out plate. These are known as "restrikes".

In this first part, we shall discuss the history and procedures of the 4 basic printing techniques:

• Relief printing

• Intaglio printing

• Planography or surface printing

Relief printing

Includes all those printing techniques in which the areas of the print that are to be left white, are engraved into the plate whilst those areas that are to be black are left in relief. They are divided into three groups:

1. Woodcuts

2. Wood engraving

3. Linocuts

1. Woodcut

History: The first sculptured stones used for prints were found in Northern China, about 1,000 years before any anything similar was used anywhere else in the world. The Chinese sealed their documents by applying a combination of different pigments on the surface of the upstanding parts of a cut out "stamp" which was then printed on silk-screen documents. This kind of stamp was the prototype of a relief engraving print, in which the non printing parts were cut away and only the upstanding parts, that were covered with a layer of paint, are printed. Only a little imagination was needed to use wood to enable bigger surfaces to be printed.

Originally wood was cut longitudinally and the first incisions were made during the T'ang dynasty (618-907) in order to spread the teaching of Buddha. The discovery that text and illustration were not difficult to multiply soon spread to East-Asia and reached Europe in the 15th century. Here it was first used to spread the teachings of the church. Each page was cut in wood (mirror-writing) and printing was done by hand. Prayer books were printed in this way and in fact enjoyed their heyday shortly before the invention of printing.

In the western world woodcuts were printed with the help of a press, with ink on an oil basis whilst in the Orient hand pressure was used together with water based ink (today even modern artists use water ink and hand pressure). Wooden incisions are characterised with their boldness and simplicity of design. Modern artists have exploited the texture of the wood grain, often deliberately coarsening the surface even further. A "chiaroscuro woodcut" is a type of print in monochrome, printed from several blocks, each linked to a different tone of the same colour. A "colour woodcut" is made by cutting several blocks and printing them in a register.

2. Wood engravings

When the design or picture is cut from a block sawed across the grain, we normally speak of it as a "wood engraving". Burins, steel tools similar to scalpels, were originally used for metal engraving. Some experts distinguish a "woodcut " from a "wood engraving" according to the tools used but more often the cutting of a block that is sawed across the grain is a more appropriate way of distinguishing.

Sharp details, delicate modelling and fine tonal variation allow the artist to cut lines (without meeting resistance by the grain's direction) and are characteristic for wood engravings. A hard and highly polished block is cut to make lines that will print white against a black background.

Max Beckmann, 1922

- Woodcut self portrait.

In the 20s, woodcut again became popular.

Artists intentionally

used the rough surface of the wood

and the harsness of the

lines

(created from this technique fighting images of battle).

The longitudinally cut blocks, used for "woodcuts", are mostly much smaller, and the veins, which stand 90° against the printing surface, hardly influence the design.

3. Linocuts

Since the discovery of this material in about 1860 and up until about 1900, it has generally been appreciated as a warm and hygienic way of carpeting. It was Frans Cisek, a drawing instructor in Vienna, that introduced the material to his pupils, explaining to them how easy it was to cut away.

With a variety of chisels he gauged the areas of the surface that were to print white and from there went on to make handmade prints. Cisek was very much opposed to the traditional ways of teaching and instead of copying the old masters, he encouraged the free use of all possible materials.

This resulted in very spontaneous and vivid expressive images, almost like children's drawings. In 1896 Vienna was shocked but fascinated. Cisek's friends, a circle of artists and architects belonging to the "Wiener Sezession group", immediately recognised the value and the possibilities of using their creativity in these works and gratefully started using the material for different purposes.

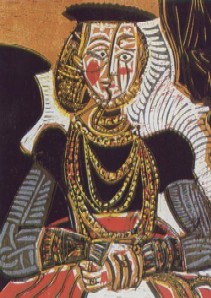

Pablo Picasso, 1958 - A linocut portrait of a woman.

Picasso wassinspired by the medieval artist Lucas Cranach

and used 6 different plates for each colours.

Linocuts were first seen as illustrations for art magazines, books and publicity material around 1900. Linocuts are popular due to the fact that hundreds of prints can be made before the plate wears out. The surface doesn't display veins, it hasn't a direction and it's easier and softer to cut than wood.

Usually it is very easy to obtain even in large measurements (200 x 200 cm, 6' x 6') and rather inexpensive. The structure of the texture is unsuitable for cutting out very fine details so that the use of other materials for these purposes still prevails.

Intaglio printing

They are all prints which are derived from inverted relief, in which the lines and forms are cut out of the surface of a plane rather than stand out from it.

Intaglio prints are made by inking the plate and then wiping its surface clean, so that ink remains only on the engraved lines. The image is transferred to a sheet of dampened paper by rolling it through a press. There are five basic techniques;

1. Etching

2. Engraving

3. Mezzotint

4. Acquatint

5. Drypoint

1. Etching

It is the most important printing process. A copper, zinc or steel plate is first coated with a "resist" or "etching ground" made from an impermeable, acid-resistant substance (nowadays it is usually varnish).

The artist draws his design on the grounded plate using a sharp etching needle. The point cuts through the dark ground to the metal beneath. To increase the visibility of the design, the etching ground is often blackened, a process called "smoking". It is done by holding the plate over burning wax tapers which deposit a coating of soot over its face.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) - A etched self portrait.

The crossed incisions tecniques is to be noted.

The greater is the light.

Once the design is complete; the plate's back and edges are coated with an acid-resistant varnish. It is then all immersed in an acid bath containing a mordant (the French word for "biting"). The most common mordant is diluted nitric acid (aqua fortis).

The mordant bites into the metal wherever the ground has been pre-pierced with the needle. The deeper the line, the darker the print but the process can be halted at any time on chosen parts by removing the plate temporarily from the bath and using a stopping-out varnish to cover and protect those lines or parts which the etcher wishes to maintain faint.

Instead of bathing the plate in acid, a coat of wax can be applied (following the traditional method). Mordant should be poured within the grooves that correspond to the incised lines .

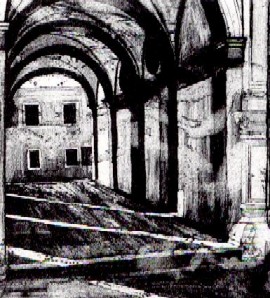

Arturo di Stefano, 1992 - San Rocco di Venezia

Etching

History.The art of etching was developed between 1450 and 1500. European craftsmen were inspired to use chemicals and techniques which were being used by the Damascene masters. They used it to decorate armour and other metal objects. Swords, knifes, helmets and shields were usually too hard to make elegant engravings. Blacksmiths used to draw decorative designs on a layer of wax, which he then applied onto the piece of armour to facilitate the drawing. An acid was used to penetrate the metal. To memorise the design he used to make a print or two from the designs which were called etchings. Soon it was discovered that one could use the same method for drawing on a copper plate.

Etching plate.

It can be seen how the lines on the plate

remain at a constant thickness.

2. Engravings

For practical reasons, Goldsmiths also soon started making prints from their designs, which were traditionally inspired by the artistically more developed Southern European countries. Goldsmiths were highly respected craftsmen as a lengthy apprenticeship was required before all necessary secrets and skills were mastered. This explains why many goldsmiths were annoyed with etchers, who, in their eyes, "only had to draw their design in a layer of wax, and let the acids do the rest"!

Economically they must have also felt threatened by the less expensive and simpler procedure required of the etchers. However engravers had some advantages with both the use of special tools (burin) and with their special skills. They could exercise more freedom in manipulating a line, swelling from thin to thick and back to thin again. Etchers could only make lines that from start to finish were as thick as the etching needle. It wasn't until the invention of a new instrument the "echoppe " in 1648 that etchers overcame this disadvantage. This instrument (a tool with an oval, bevelled point) enabled lines to be cut into the plate or ground of varying width, imitating the swelling or tapering along their lengths, thus imitating the engravers lines.

Later, goldsmiths used a black compound of metallic alloys to decorate metal surfaces (mixture of silver, lead and sulphide). Worked into incised lines, it was fused by heat and then polished to give the design a more permanent character.

A problem that both etchers and engravers shared was the limits their techniques had in making smooth, overlapping areas from dark to light. Who else but Rembrandt, master of light and shadow, could overcome this problem. As in painting, he also succeeded in etching, to create shadow and light in a dramatic way. He was also the first to integrate his figures into a landscape, unlike in all previous etchings, where figures seemed to stand out in front of a background.

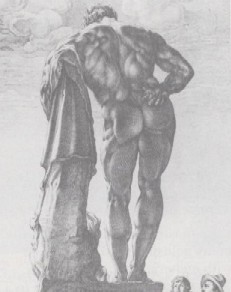

Henrick Goltzius, 1957 - Ercole Farnese - Bronze incision.

This type of bronze incision was used for appriximately two

centuries

for recreating souvenirs of works of art and

reproductions

of classics buildings that had been

purchased by travellers.

Ir is clearly seen of lines are

easily able to be increased and decreased in thickness.

3. Mezzotint

The next step was the invention of the mezzotint technique, discovered by a German officer Von Siegen whilst working in Amsterdam, strangely enough very near Rembrandt's studio. A copper plate is scored with a rocker, (invented in the 17th Century by Abraham Blooteling) which creates a uniform burr over the whole surface. The design is formed by smoothing and polishing the areas which are to print lighter, with a burnisher and scraper.

Carlo Lasinio, 1783 - Portrait of Eduard Dogoty

Mezzotint became a very important technique

for reproducing paintings.

The smoother the surface, the less ink it will take, so that mezzotint is capable of all tonal graduations from black to white. Widely used in the 18th and 19th Centuries for reproducing paintings, it became such a popular reproductive technique that it finally ended up being used for newspaper cliché (photo engraving and photogravure) making it difficult to survive amongst the artistic techniques. Being essentially tonal as opposed to linear medium, mezzotint is particularly suitable for obtaining colour prints.

4. Aquatint

A form of etching which is not confined to the use of line only but is capable of tonal effects in a similar way to those of wash drawing from which it gets its name The transparent tones are obtained by using porous ground through which the acid can penetrate.

A copper or zinc plate is first dusted with a fine sprinkling of powdered resin usually by means of a dust box to ensure an even covering. This is then carefully fused to the metal by heating so that the mordant in the acid bath will bite around each grain causing the plate to be pitted all over with little dots.

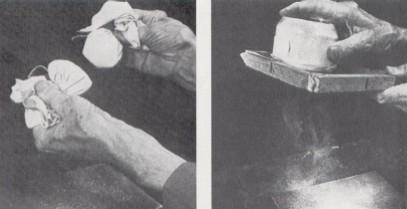

Aquatint.

There are different ways to distribute powder resins.

Using either cloth bags (left) or a dust box (right).

These, when inked, result in an uniform, grainy-toned print. The amount of resin powder used, its coarseness and the length of time the plate is immersed in the bath all regulate the depth and texture of the tone. The artist can achieve a variety of tones on the same plate by "stopping out" some areas, protecting them from further attack from the acid, while biting others more deeply. This process can be repeated until a large number of different tones have been obtained. Areas that are to print completely white have to be "stopped out" before the first immersion in the acid bath.

5. Drypoint

This is a method of intaglio engraving in which the design is scratched directly on to a copper plate with a sharp tool (which is sometimes tipped with a diamond). Drypoint is the least complicated of all the intaglio techniques though its subtleties are amongst the hardest to master. Its particular qualities lie in the burr that the needle throws up along each side of the furrow as it cuts into the metal. This holds the ink when the plate is wiped and gives the printed line a furry softness that is much valued. The deeper the line, the blacker it will print.

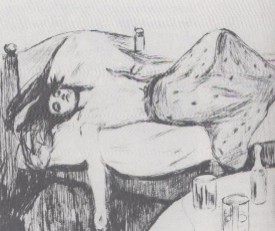

Edward Munch, 1985 - The day after

Drypoint

Munch, better known for his woodcuts, uses the dramatic

effect

of drypoint for highlighting the nuisance created from

light

and noise the morning after a terrible drinking session.

This makes drypoint a very direct and sensitive medium in which tonality can be achieved by touch alone. A drypoint plate can produce only a few satisfactory impressions because the pressure of the press flattens the burr. Drypoint may be used for putting the finishing touches to etchings or for lightly marking out the design for a line engraving before setting to work with the more cumbersome burin.

The plate mark

This is the impression left by the edge of a block or plate when a print has been put through a press. It is therefore an indication that the print is pulled from an original plate as opposed to a reproduction. However, a plate mark can be artificially impressed into the paper to simulate an original impression.

Planographic

Lithographs

Lithography is the major form of planographic or surface printing, a process in which proofs are pulled from a surface which is neither incised nor raised in relief but perfectly flat.

The design is drawn on the surface of a limestone. Invented by Alois Senefelder in 1798, the process is based on the principle that grease and water repel each other. The artist draws his design on a heavy slab of flat, fine-grained limestone using either special ink or a special lithographic crayon composed of wax, soap and lampblack.

The stone is then treated with a variety of chemical solutions which fix the grease in the drawing and enhance the porosity of the blank areas so that when water is applied, it is immediately repelled by the grease but accepted by the bare stone surface. Greasy ink is next spread over the stone with a roller. It in turn, adheres only to the grease of the drawing. The other areas, being damp, repel it, making it possible to pull prints from the inked stone.

Offset

It is the most popular technique used today although used mainly for industrial purposes. It can be defined as a modern development of lithography.

The lithograph stones are replaced by a metal sheet on which the image is transferred via a photographic procedure. The sheet is then passed through ink and dampened. The image is printed on a rubber plate which is then used to print thousands of copies on paper.

Serigraphy or silk-screen printing

A modern development of stencil printing. Paint is applied with a squeegee through a fine silk screen held taut in a wooden frame and masked in places by a stencil or impervious lacquer. By the use of successive stencils, colour prints can be made. The process is mainly used commercially but is also used by artists for producing original prints. The advantages of the process are that the image is not made in reverse (as in most types of printing) and the artist does not have to use ink.

Serigraphy or silk-screen is a rather cheap, easy and quick technique. It is not suitable for fine effects and refined details. Lichtenstein, like many other pop artists, used it to give his art an impersonal feel about it and to highlight the current narrow minded materialistic period.